We went to the MAC during the Montreal Biennale (BIAN) to see (and taste) the Hedonistika Montreal show. A congregate of artists, researchers, chefs and scholars, Hedonistika offers a critical outlook on the relationship between food and technology (and how does the latter affect the former for better and worse) in often fun and creative ways.

What struck me is the sheer intimacy of most of the experiences with the works; feeder robots spoon-fed us strange and unusual mixes (mine tasted like either kefir or spicy mayo), artists swallowing cameras to document the digestion of their food (The Fantastic Voyage, by Stefani Bardin) and scanning audience members’ faces with a hacked Kinect in order to 3D print their portraits (The Bliss Point) all established intimate relationships with us, as taste is a very intimate sense, as we need to ingest food in order to experience taste. Being fed by a robot was an unusual experience, as I felt that we had to trust the machine not to accidentally hit us, let alone to trust it enough for it to give us a random puree designed to have an unusual taste.

Hedonistika offered a playful and critical way of presenting food–especially in the context of an exhibition, which is something that does not happen often–and it was a well-balanced counterpart to the rest of the exhibition, as BIAN focused primariy on audiovisual works; many of the installations were perhaps immersive, but they were not interactive. Such was the case of Signal To Noise, which, despite it being one of my favorite pieces in the exhibition, did not so much ask to be interacted with as much as to stand and let ourselves be passively immersed.

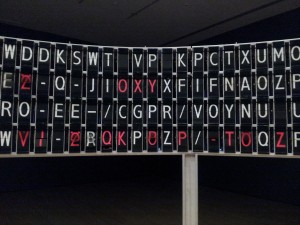

Signal To Noise is a kinetic sculpture that uses split-flaps depicting letters, which are shuffled in what I initially perceived as a random order, until I noticed that on occasion the letters formed words scattered among the “noise” generated by most of the other letters that spilled gibberish. The very noise generated by those split-flaps as they rotate (with the help of several servo motors) was overwhelming, and the entire installation strongly referenced Shannon and Weaver’s mathematical model of communication, which is still prevalently used in communication studies to this day. Shannon and Weaver’s model describe communication as a message being encoded by a sender, then wrapped in a medium and in turn decoded by a receiver, which gives feedback to the message’s sender. However, throughout the model of communication there is always noise–either the sender didn’t encode his message right, or the receiver doesn’t understand, or there is interference as they communicate, like two people trying to speak in a loud room–and the more information there is in the process of communication the more likely there is to be noise. Signal to Noise reflected that model elegantly, in my opinion, and it was an immersive experience, although I would have liked to be able to interact with it somehow.

In contrast, The Blind Robot was a very intimate interactive experience that dealt with touch and being touched.

The Blind Robot invites the audience to sit and be touched by a pair of robotic hands, in a manner reminiscent of how blind people touch to explore faces and objects. At first, the touch feels intrusive and very uncomfortable–I felt like I had taken a dip in the Uncanny Valley, where the object resembles a human in behavior but something feels wrong about it– but after a while I grew comfortable with the machine, and even started to almost give it human characteristics as if it were a real person. Furthermore, I didn’t have to simply sit passively as the machine did its work, as I could tap my shoulders or my face, and the blind robot would then put its hands where I had previously left them. The Blind Robot played effectively with touch and proprioception, and it’s hard not to feel for the robotic arms on my shoulders.